The art world is buzzing this week with some major news: a rare portrait of a African prince by Gustav Klimt, missing since 1938, is causing a sensation at the Tefaf Maastricht, the world’s leading European fine arts and antiques fair.

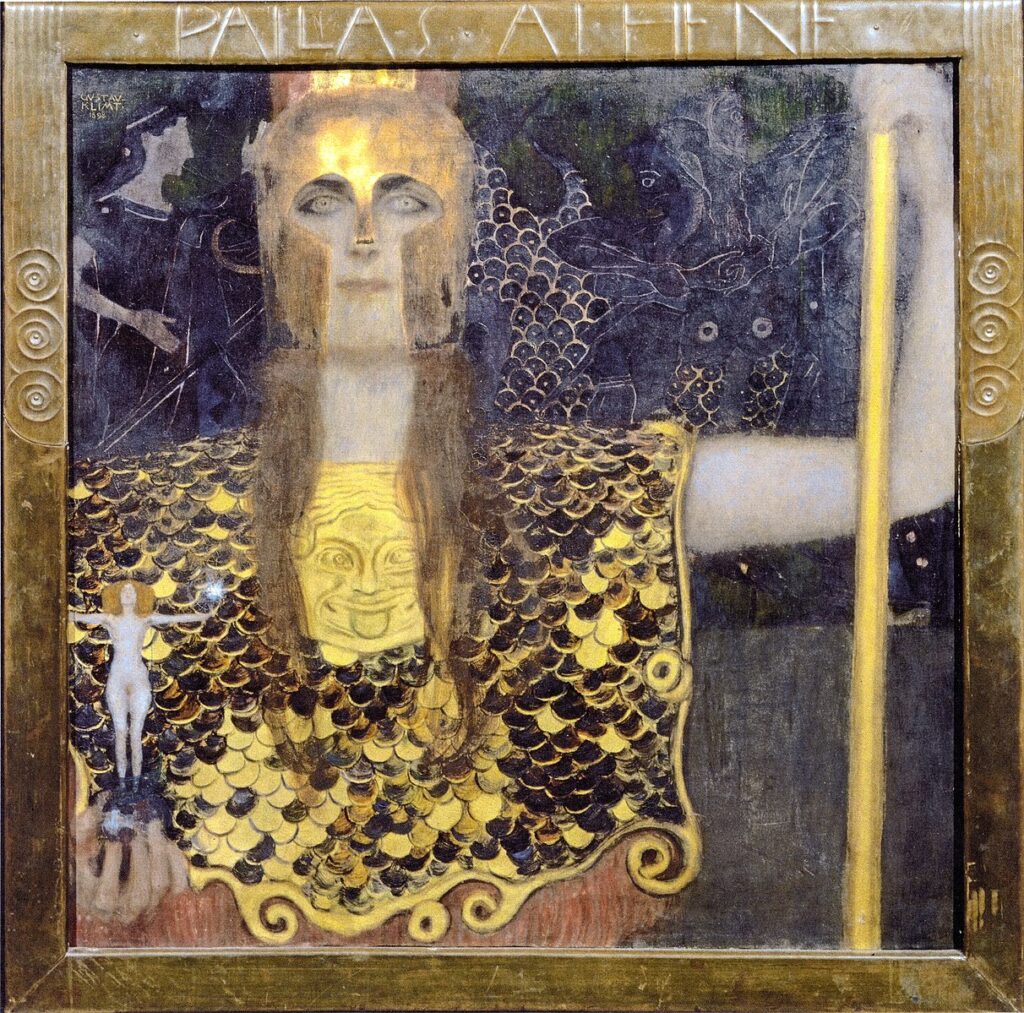

When we think of Gustav Klimt, the images that immediately come to mind are:

and…

or even…

In short, we think of Klimt, the Austrian Symbolist painter, one of the most prominent figures of the Art Nouveau movement, known for his vibrant characters set against golden backgrounds, an instantly recognisable style from his famous Golden Phase in the early 1900s, shortly after he broke away from academic art traditions.

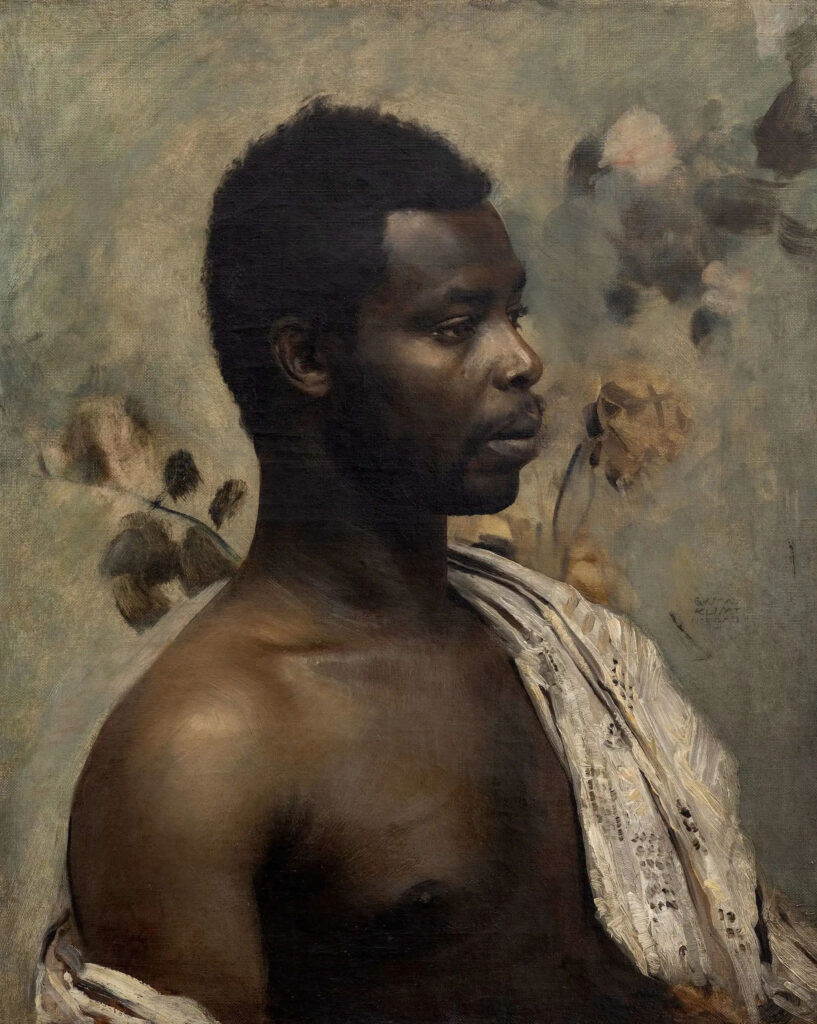

So, when this 1897 portrait of an African Prince reappeared after decades of disappearance and mystery, the astonishment and wonder were palpable :

There has been a lot of buzz surrounding the story of this painting, how it was lost and then recovered, and how the Wienerroither & Kohlbacher Gallery is offering the restituted artwork for $16.4 million.

I was struck by the beauty and power of this painting.

It’s a truly magnificent and poignant work, portraying a Black man with remarkable sensitivity, finesse, and tenderness. Unusual for an Austrian piece from 1897.

In this article, I want to focus on the key aspects that, in my opinion, make this masterpiece so remarkable.

The rediscovery of Klimt’s magnificent African Prince

With astonishment, the world is rediscovering the magnificent portrait of an African prince by Klimt (1862–1918). Dated 1897, this youthful work has just been rediscovered after nearly a century of disappearance.

Presented by the Vienna-based gallery Wienerroither & Kohlbacher (stand 609), this oil portrait depicts Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona, a member of the royal family of the Osu tribe in Ghana, whom Klimt met at a folklore exhibition in Vienna.

At least, this is the sanitised version many media outlets will report.

The painting “reflects a pivotal moment in Klimt’s artistic evolution” and “provides valuable insight into his stylistic shift,” notes the W&K gallery. It combines a figure depicted in a very realistic manner with a plain background from which emerge a few floral motifs. The artist paid particular attention to the volumes, skin tones, and the model’s expression, which is both gentle and pensive.

Infused with respect and humanity, its rediscovery comes at a fitting time, in an era facing both a resurgence of racism and a renewed interest from museums and much of the public in bringing to light the stories of those who have been marginalised in art history: African people, who were long deemed unworthy of being painted, or, when represented, were shown in a stereotypical manner.

Klimt met Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona in a human zoo

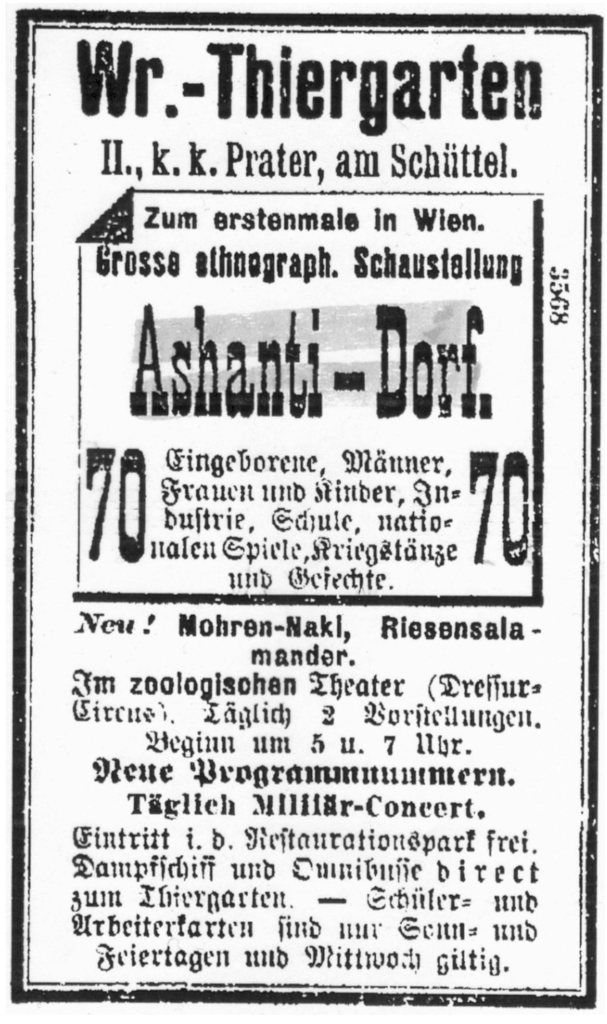

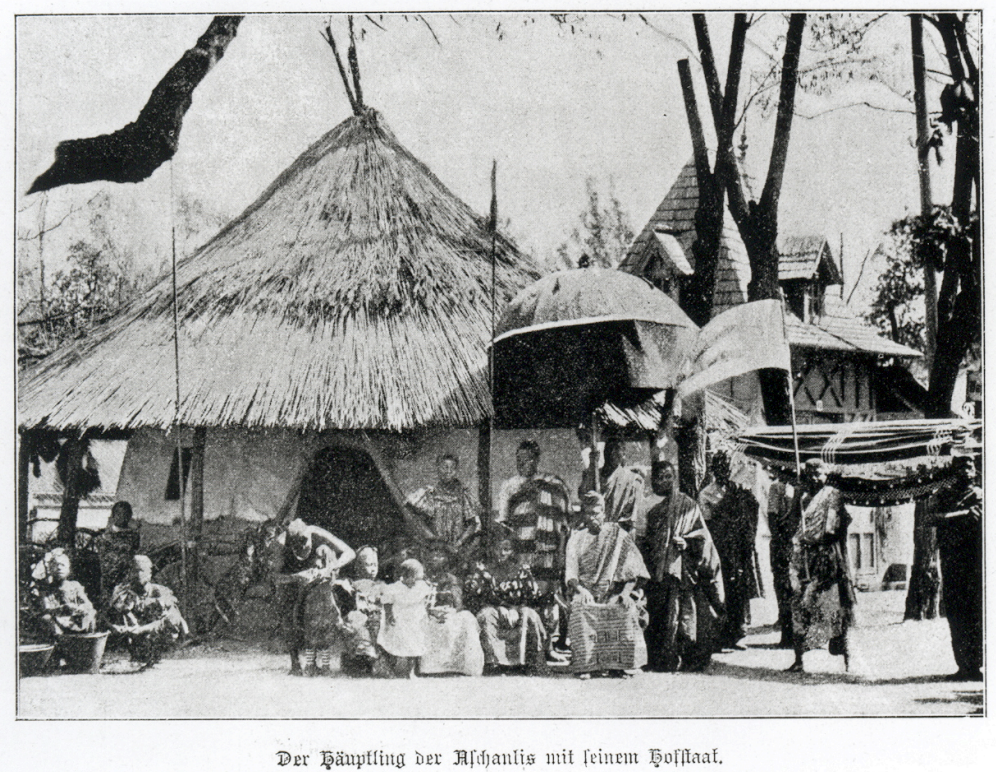

The portrait of Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona was created after Klimt and his lifelong friend, fellow artist Franz Matsch, attended a popular event at the Tiergarten am Schüttel ; a zoo that also hosted ethnographic exhibitions where people were put on display. A human zoo.

The first Ashanti exhibit ran from July to October 1896 and sparked what became known as the “Ashanti fever” among the people of Vienna. The exhibit drew around 500,000 visitors, with daily attendance reaching 5,000 to 6,000. This financial success saved the Tiergarten from bankruptcy, leading to the Ashanti being rehired in 1897.

Although the exhibition was billed as showcasing representatives of the Ashanti people, an ethnic group from present-day Ghana that was then under British colonial rule, the individuals on display were actually members of the Osu people.

For this specific exhibition, around 120 Osu people travelled to Vienna by mail steamer, where they were exhibited to crowds. The exhibit was inaccurately titled The Gold Coast and Its Inhabitants: Ashanti. The event gained significant media attention, and the Osu people were even invited to various social events at theaters and coffeehouses in Vienna.

The location of the Tiergarten, literally “Zoological Garden” in German, was no accident. Marketed as an educational, anthropological experience, the Völkerschau (ethnographic exhibit) allowed Viennese citizens to observe “the primitive other” in what was supposedly an authentic setting, reinforcing their cultural superiority. However, the real fascination lay less in the anthropological aspect and more in the allure of the exotic, which was heavily charged with an element of eroticism.

The texts of the time about the Ashanti people, such as those by writer and poet Peter Altenberg, often reflected an inherent white male gaze. Though intended to be well-meaning and framed as protective paternalism, they ultimately imposed themselves on the bodies of African women, much like colonial powers encroached upon and seized foreign lands.

I wanted to highlight this because reading media reports claiming that Klimt simply met an African prince at a folklore exhibition in Vienna feels like a misrepresentation of history, and frankly, poor journalism.

The history of Gustav Klimt’s portrait of African Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona: from 1897 to 2025

‣1897: At the event, Klimt and Matsch were likely commissioned to paint a portrait of the same Osu prince. Klimt’s canvas was left unsigned and remained in the studio after its completion, suggesting that the commissioning client preferred Matsch’s version. Klimt painted Prince William in profile, while Franz Matsch captured him almost frontally. The much more conventional portrait by Matsch is now housed in a museum in Luxembourg. Klim’s painting is believed to have remained with him until it was offered at auction after his death in 1918.

‣1923: Klimt’s painting was offered at Vienna’s Samuel Kende auction house as “Portrait of a Negro, in three-quarter profile facing right, with a white coat around his shoulders,” with a starting price of 15,000 crowns (1160USD in 2025). It is not known whether it sold.

‣1928: Ernestine Klein was listed as the owner when the painting was exhibited at a memorial show for Klimt at the Vienna Secession. Klimt had died in 1918. Ernestine and her husband, Felix (a wine wholesaler), had converted the artist’s former studio into a villa.

‣1938: Due to their Jewish heritage, the couple fled Austria when the Nazis took control, eventually living in secret in Monaco. They spent the last year of the war in a safe room. Upon her return, Ernestine discovered that some artworks had been stolen.

The painting disappeared and was unaccounted for until it resurfaced in…

‣2021: A couple of collectors unexpectedly brought a poorly framed, heavily soiled painting with a barely visible estate stamp by Gustav Klimt to the W&K, Wienerroither & Kohlbacher gallery. Art historian Alfred Weidinger, author of the artist’s catalog raisonné (inventory of an artist’s works) in 2007, confirmed that it was the long-lost piece that had been sought for years.

‣2023: The Belvedere, the Wien Museum, and the Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf had all returned artworks to the heirs. After intensive negotiations, a restitution agreement was finally reached with Ernestine Klein’s heirs. The Federal Monuments Office also approved the export, allowing Klimt’s portrait of the African prince to be displayed at the world’s most important art and antiques fair in Maastricht until March 20.

‣2025: Viennese art dealers are now presenting the painting from a private Austrian collection at the TEFAF art fair in Maastricht, the Netherlands. The painting caused quite a stir at the preview on Thursday. It will be interesting to see whether a new owner will be found soon for this magnificent piece, which is being offered for 15 million euros.

What’s truly beautiful about this portrait is that Klimt, an Austrian artist from the late 19th century, offered us a majestic gaze upon a Black model.

This painting, which Klimt kept until his death, is the only known portrait of a Black person in his entire body of work to date.

I think it’s difficult to fully grasp today just how rare this was in that context and at that time. (It’s worth remembering that Klimt was a rebel, after all).

We know very little about the private moments surrounding the creation of this portrait; Klimt didn’t keep a diary. Yet, I would have loved to know everything. I like to imagine him visiting this exhibition like an ordinary Viennese citizen, curious about the ‘Ashanti fever’ that was electrifying the city, and realising the beauty of the people who were there, and the odious ideology that consisted of exhibiting them in those conditions. I like to imagine him deciding to create the most beautiful portrait possible to restore this prince’s dignity. Spending long hours with him, discussing life.

That would make a magnificent film. Unfortunately, we know nothing. But this portrait makes me dream. And you?

I am a French-New Zealand artist, born in Paris and living in Wellington since 2017. As a painter and sculptor, I have been passionate about art and history since childhood. I was fortunate to grow up surrounded by magnificent artworks, endless curiosities, the timeless scent of old stone, and a continent rich in stories and mysteries.

Studying history of art along with my interest in psychology and writing led me to create this blog, where I share my perspective on topics and questions that intrigue me. Occasionally, I allow myself a more personal post. I hope you enjoy reading my articles as much as I enjoyed writing them.

You can browse my work at www.lauraolenska.com or join me in my creative process on Instagram @lauraolenska.